Here’s Your Chance to Have a Say: How Can Federal Agencies Best Reform Their Environmental Review Process?

The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) is considering modernizing its regulations prescribing the process federal agencies must follow in reviewing the environmental impacts of their actions under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). That process has long burdened applicants for some federal permits with delays of many months or even years. The CEQ has solicited public comment on “potential revisions to update the regulations and ensure a more efficient, timely, and effective NEPA process.” It seeks comments by July 20, 2018; given the broad scope of the CEQ’s proposal, requests to extend that deadline are likely.

Background

Enacted in 1970, NEPA generally calls on federal agencies to ascertain, disclose, and consider the environmental effects of their proposed actions before undertaking, funding, or permitting them. The surprisingly short statute speaks in generalities, leaving much of its practical requirements to be spelled out in regulations adopted by the CEQ. The CEQ adopted its current regulations in 1978—when environmental impact assessment was in its infancy, environmental documents were issued on paper, and the internet was but a futuristic prediction—and has since substantively amended them only once, in 1986, to make a specific adjustment (i.e., drop a requirement for “worst case” analysis).

While NEPA compels federal agencies to take a hard look at the environmental consequences of their proposed actions, it does not direct them to reach any particular decisions on those actions, including whether to mitigate adverse environmental effects. After reviewing environmental issues in compliance with NEPA, federal agencies generally are free to make whatever decisions they want regarding their proposed actions, provided of course that those decisions comport with the requirements of any other applicable laws. In this respect, NEPA is regarded primarily a “procedural,” rather than “substantive,” statute.

While NEPA directly governs only federal agencies, it effectively regulates many actions of private persons as well as state and local governments. The act generally applies to any activity undertaken, funded, or permitted by a federal agency that affects the environment. Given the pervasive involvement of federal agencies in private, state, and local activities, NEPA reaches many land use and development projects. NEPA applies, for example, whenever the Corps permits a landowner to fill waters or wetlands for housing or other uses, whenever the Forest Service approves timber sales in national forests, whenever the Federal Highway Administration helps build a highway or interchange, and whenever the Bureau of Reclamation authorizes the sale of water for agricultural or other uses.

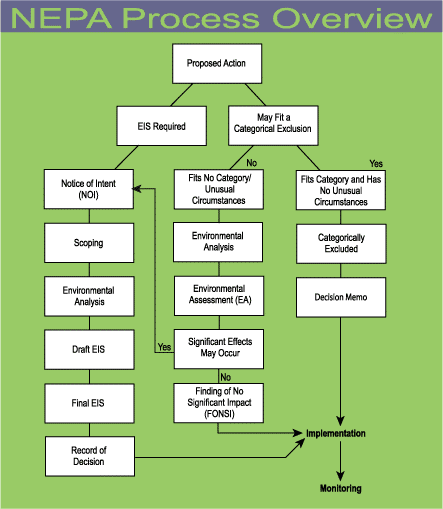

The NEPA process can usefully be summarized in four basic steps: (1) determine whether NEPA applies, (2) determine whether to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) or, alternatively, a brief Environmental Assessment (EA) to review the environmental effects of a proposed action, (3) prepare the appropriate environmental document, and (4) make a decision on the proposed action based on the considerations discussed in the EA or EIS.

NEPA Process

If NEPA applies to a proposed action, an agency must determine whether its action may “significantly affect the quality of the human environment” and thus whether to prepare an EA or EIS. Because the term “significantly” marks the threshold for requiring an EIS, it is the most litigated and discussed of all NEPA’s terms. The term is not readily reduced to a simple formula or precise metrics. Congress did not define it, and courts and commentators have, largely of necessity, generally elaborated on the term with respect to specific facts. Taking its cue from the general thrust of these fact-specific explanations, the CEQ currently defines “significantly” in terms of “context” and “intensity” and offers a nonexclusive list of factors to consider.

If an agency prepares an EIS, that document must provide a full and fair discussion of significant environmental impacts and must inform decision-makers and the public of reasonable alternatives that would avoid or minimize adverse impacts. The CEQ says that it should be analytic, not encyclopedic, and concise—no longer than necessary to comply with the act. While the CEQ has prescribed 150 pages as the normal limit and 300 pages for proposals of unusual scope or complexity, in practice EISs generally range from several hundred to several thousand pages. Typically prepared by a multi-disciplinary team over a period of several years, EISs commonly cost several hundred thousand to several million dollars.

Executive Order

On August 15, 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13807, “Establishing Discipline and Accountability in the Environmental Review and Permitting Process for Infrastructure Projects.” That order calls for federal agencies to develop a coordination process that enables multiple agencies to reach “one federal decision” on each major infrastructure project and, moreover, develop ways to reduce the time to complete environmental review and authorization decisions on such projects to an average of approximately two years—an ambitious goal given that something closer to a decade is more typical for such projects under current procedures. The order also directs the CEQ to develop regulations and guidance as it deems necessary to “ensure optimal interagency coordination of environmental review and authorization decisions [and] ensure that [such reviews and decisions] involving multiple agencies are conducted in a manner that is concurrent, synchronized, timely, and efficient.”

CEQ Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Toward that end, the CEQ on June 20, 2018, published an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) inviting comments on twenty subjects covering nearly every aspect of its regulations. Among the subjects flagged are:

• Coordination Among Agencies. Should regulations ensure that review and decisions by multiple agencies are conducted in a manner that is concurrent, synchronized, timely, and efficient? Is so, how?

• Use of Prior Studies. Should regulations promote efficiency by facilitating agency use of earlier environmental studies, analyses, and decisions?

• Document Size and Format. Should regulations about the length and format of environmental review documents be revised? Such documents often far exceed the length recommended in the current regulations.

• Time Limits. Should regulations provide time limits for completing environmental review documents? Should regulations address the timing of agency actions?

• Definitions of Key Terms. Should existing definitions of key terms—major federal action, effects, cumulative impact, significantly, and scope—be revised? Should new definitions be added for terms such as alternatives, purpose and need, reasonably foreseeable, and trivial violation? Definitions of key terms such as these often drive the decisions of agencies and courts about how NEPA should be applied in various circumstances. Substantial changes in these definitions could greatly affect decisions about whether environmental review is required or, if so, what kind of review, e.g. preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) or Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI). The point of defining “trivial violation,” not explained in the ANPR, may be to suggest that courts should address substantial issues without nitpicking NEPA documents and proceedings.

• Contractors. Should regulations about agency responsibility and preparation of documents by contractors and project applicants be revised?

• Alternatives. How should regulations address the range of alternatives that should be considered and which alternatives may be eliminated from detailed analysis?

• Anything Else. The CEQ invites comments on “general” subjects, including rescinding or revising any obsolete regulations, updating regulations to reflect new technologies, improving efficiency and effectiveness, clarifying the role of tribal governments, reducing unnecessary burdens and delays, and revising regulations about mitigation of environmental impacts.

The CEQ’s invitation offers an opportunity for those in the regulated community—industrial, commercial, and agricultural businesses, state and local governments, environmental and engineering consultants, and lawyers—to help shape the nature and scope of regulatory reforms the CEQ appears poised to propose. If and when the CEQ proposes specific regulations (likely months from now), there will be further opportunities to weigh in, but comments then will naturally focus on those specific proposals, rather than the broad sweep of possible reforms currently under consideration.

David Ivester

Briscoe Ivester & Bazel LLP

155 Sansome Street, 7th Floor

San Francisco, CA 94104

Telephone: (415) 402-2700

Fax: (415) 398-5630